‘The Very Beautiful Sight’ –

Exploring the Aesthetic of C. T. R. Wilson’s Cloud Chamber Photographs

Murdo Macdonald

This is an edited and expanded version of a presentation given on 4 July 2015, at Highland Institute for Contemporary Art, Dalcrombie, near Inverness, at the exhibition: Wilson Chamber Images: The Aesthetic of the Sub-Atomic. http://www.h-i-c-a.org/ctr-wilson—murdo-macdonald.html An early print version was published by HICA. The version published here is broadly as it appeared in print in The Scottish Society for the History of Photography: Studies in Photography, Summer, 2017. Updated, and more images added, 2021.

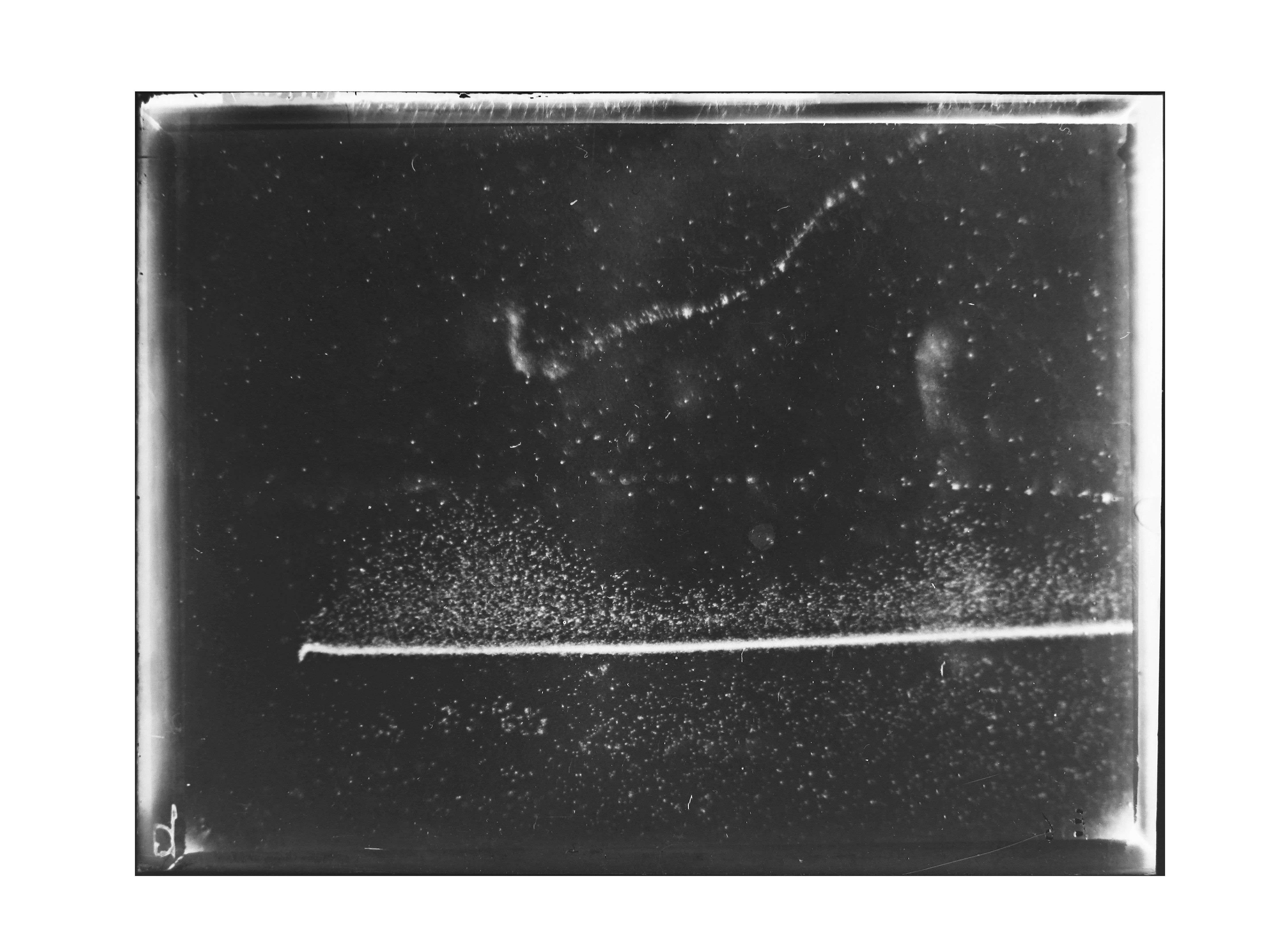

Print from the original glass plate negative made by Wilson for his pioneering 1912 paper published by the Royal Society. [All images courtesy of The Royal Scottish Academy, Andrew Wilson Collection, or the author].

C. T. R. Wilson was one of the most remarkable of all Scottish scientists of the twentieth century. Photography was central to his achievement. He had a keen eye for the beauty of the phenomena he photographed, and he had the technical ability to produce outstanding results. In 1911 and 1912 he published photographs that showed the tracks of elementary particles of matter for the first time. Those images have intrigued me since I first saw them many years ago. In 2013 I went in search of the original glass plate negatives.

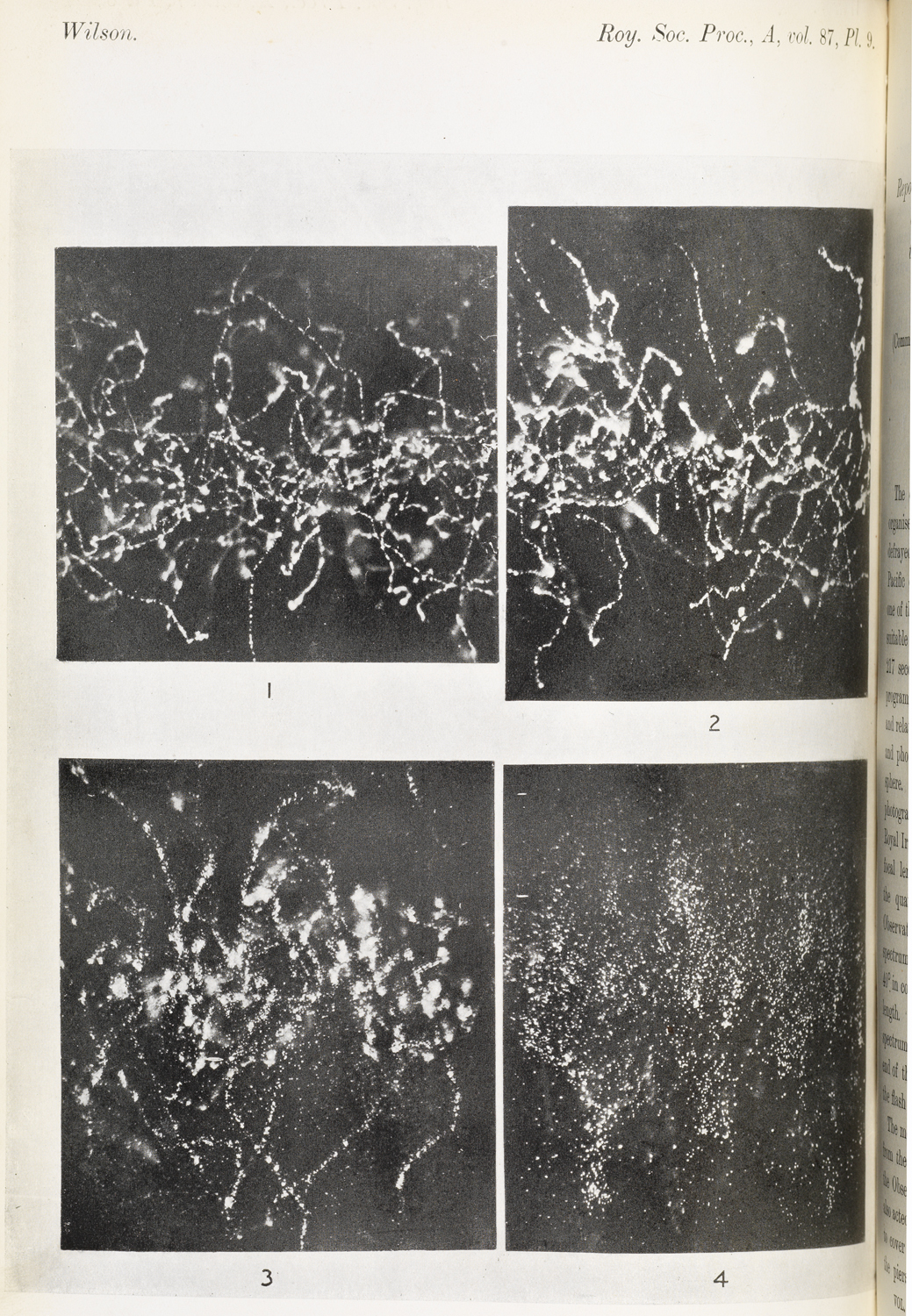

Images from Wilson’s 1912 paper for the Royal Society

But first some background. Wilson was born in 1869 at Crosshouse Farm in Glencorse in the Pentland Hills just south-west of Edinburgh. He is commemorated at nearby Flotterstone in a plaque erected by the Institute of Physics and the Royal Meteorological Society. He was educated in Manchester and Cambridge and spent his career working at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, following in the footsteps of his fellow Scot, James Clerk Maxwell. In due course he retired to Edinburgh where his friend Max Born was professor. Later he moved to Carlops, not far from his birthplace, and there he died in 1959. He was one of the leading physicists of his generation, awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for 1927 for his work in making visible the tracks of sub-atomic particles. In that same year one finds him pictured along with Albert Einstein and Marie Curie in the front row of a photograph taken at the Solvay Conference in Brussels. Max Born and Niels Bohr are just behind him. Others present included Lorentz, Dirac, Planck, and Heisenberg. It is one of the most important group photographs in the history of science.

Crucial to Wilson’s work was a period in 1894 which he spent studying cloud formation from the observatory on the summit plateau of Ben Nevis. That experience led to his invention of what became known as the Wilson Cloud Chamber and in due course that apparatus transformed the possibilities not simply of studying cloud formation, but of tracking the elementary particles of matter, which left tracks of ‘cloud’ as a result of their ionisation. It was so successful in this latter regard that the cloud chamber was described by Wilson’s fellow Nobel laureate Ernest Rutherford as ‘the most original and wonderful instrument in scientific history.’

Information for the 2015 exhibition at HICA

Wilson’s brilliance as a technical photographer and the sheer beauty of his photographs has been little appreciated outside physics. This paper is part of the effort to change that. I have developed it from a presentation given on 4 July 2015 at HICA (Highland Institute for Contemporary Art), Dalcrombie, near Inverness. The occasion was the opening of the exhibition: Wilson Chamber Images: The Aesthetic of the Sub-Atomic. The purpose of that exhibition was to draw attention to Wilson’s work not only as a scientist but as a pioneering photographer who created some of the most beautiful and intriguing images of the early twentieth century. The exhibition was conceived as an exploration of Wilson’s photographs from 1911 and 1912 and it acted as a focus for discussion of both art and science. Of particular note was a talk given by Alan Walker of the Institute of Physics and the University of Edinburgh in which he traced analogies between the work of James Clerk Maxwell, C. T. R. Wilson and Peter Higgs.[1] A particularly engaging aspect of that talk was the almost identical peer recognition given to Wilson and Higgs over their careers, culminating in both cases in the Nobel Prize.

Alan Walker lecturing on Wilson and Higgs at HICA in 2015

I am not a scientist. If I would describe myself as anything I am a visual thinker. I had no real sense of mathematics until I saw a visual proof of Pythagoras’ Theorem. Now, having studied the practices of painting and the theories of psychology, I find myself an art historian. I am not particularly interested in aesthetics from a philosophical point of view. But ‘aesthetic’ is an interesting word. It is interesting because it implies feeling. So my question was: what, for me, is the feeling of photographs by C. T. R. Wilson, and how might one approach that question of feeling, of the aesthetic in his work? I tried to answer that question for myself by presenting in the exhibition at HICA both enlargements from photographs by Wilson himself and photographic responses to those prints, as sampled by myself.

I have been thinking about issues of art and science for most of my life. In 1986 in my PhD thesis I wrote about what I called the inappropriate separation of science and the aesthetic, and I want to revisit some of that thinking here. While aesthetically good notions like balance and symmetry tell one a great deal about what constitutes good art they tell one equally what constitutes good science. You can respond to a drawing by Leonardo by losing yourself in it as a work of art or by using it as a tool of analysis for your scientific thinking, but it is a wonderful work of drawing either way. It has an aesthetic effect on us, whether we see it for its precise scientific observation and visual hypotheses, or for the ambiguity that characterises it as a work of art. Similarly a great equation such as Einstein’s E=MC2 is no less aesthetically pleasing than a painting by Mondrian or Claude. They each depend on elegance, balance and coherence. When I was studying for my PhD I found William J. Kaufmann’s illuminating introductory book, Relativity and Cosmology, in which he considered Einstein’s work to have aesthetic ‘validity’ over its competitors. Kaufmann writes: ‘It should, however, be pointed out that, mathematically, Einstein’s theory is extremely simple and beautiful. The competing theories are not. If beauty and simplicity are in some way a measure of validity, we may continue with confidence in assuming Einstein was right.’(Kaufmann, 1977: 36)

So beauty and simplicity, feelings of elegance if you like, or, as we might say, aesthetic ideas, are for Kaufmann at the heart of scientific judgment. No surprise there, but it begins to shift the colloquial use of the word ‘aesthetic’ away from the sole province of art. A stimulating discussion of the importance of such beauty in science can be found in the writings of Paul Dirac. He goes even further than Kaufmann, holding that the primary test of a scientific theory is its beauty: ‘It is more important to have beauty in one’s equations than to have them fit experiment.’ (Dirac, 1963: 47). He says of Einstein’s theory of gravitation: ‘one has an overpowering belief that its foundations must be correct quite independent of its agreement with observation.’ (Dirac, 1980: 44). And again of Einstein: ‘He was guided only by the requirement that his theory should have the beauty and the elegance which one would expect to be provided by any fundamental description of nature. He was working entirely from these ideas of what nature ought to be like and not from the requirement to account for certain experimental results.’ (Dirac, 1981: 79). It is, however, unfortunately true that culturally we are not encouraged to appreciate the beauty of science, or rather that beauty is somehow hived off into the province of art not of science. But that is a function of our contemporary cultural reality not of beauty. So my point is one that I find very obvious: namely that aesthetic criteria unite art and science rather than uniquely specifying art.

That is about as far as I got in my PhD in 1986, but I have been exploring the aesthetic unity of art and science ever since. The work of C. T. R. Wilson has been central to that exploration for as long as I can remember, but I do not remember exactly when Wilson began to figure for me as a name. By the end of the 1970s I had become aware of the bubble chamber photographs used by Fritjof Capra in The Tao of Physics, and also one used by C. H. Waddington in Behind Appearance, in which Waddington explored modern science through modern art and vice versa. Capra’s analogies between the new physics and spiritual metaphors for cosmic energy such as the dance of Shiva are still of current interest. Indeed it is because of Capra’s influence that a statue of the dance of Shiva was erected at CERN in 2008.

I eventually realised that the primary sensor for particle physics for the first half of the twentieth century, the absolutely crucial period in the development of the discipline, was not the bubble chamber at all, but its predecessor, the cloud chamber, and that the cloud chamber had been developed by a Scot called C. T. R. Wilson. Wilson seemed to be a remarkably forgotten figure considering his importance. Part of that forgetting of Wilson seemed to be bound up with the fact that very few cloud chamber images were easily available, in contrast to numerous bubble chamber images and, more recently, images from computerised sensors at CERN.

One can find an example of such ‘missing’ cloud chamber images in a book by John Barrow entitled Cosmic Imagery: Key Images in the History of Science. Wilson’s importance is acknowledged in the text and Barrow’s chapter title, ‘Writing on Air,’ obviously refers to Wilson’s cloud chamber work, but in spite of that the image that illustrates the ideas is a bubble chamber image, not a cloud chamber image. It is not as if Barrow is not taking Wilson seriously. Indeed he writes that ‘These observations gave us the first concrete look at the smallest particles of matter …. The cloud chamber led to many dramatic discoveries …’ (Barrow, 2008: 495). Barrow goes on to quote from a memoir of Wilson by another notable physicist, P. M. S. Blackett. Blackett received a Nobel Prize for his work with the cloud chamber in 1948, twenty-one years after Wilson’s Nobel Prize. Blackett wrote after Wilson’s death was this: ‘Of all the scientists of this age, he was perhaps the most gentle and serene, and the most indifferent to prestige and honour. His absorption in his work arose from his intense love of the natural world and from his delight in its beauties.’ (Blackett quoted by Barrow, 2008: 495).

It was only in 1952 that the bubble chamber was invented. That period of over forty years between Wilson’s first successful cloud chamber photographs in 1911 and the invention of the bubble chamber simply emphasises the significance of cloud chamber images during the critical period of development of twentieth century physics. So what’s going on here? One answer I would suggest is the obvious one, namely that Capra’s book The Tao of Physics was so successful that people tend to look no further than the imagery that he used.

The reason that Capra used bubble chamber imagery was that he was writing in the 1970s, and there was a lot of very beautiful bubble chamber imagery available at the point. Capra wasn’t trying to write a history of science he was popularising ideas and very effectively. I can’t complain about that because Capra helped to introduce me to the whole topic, and that eventually led me to Wilson. What is interesting now is that while, if I understand it rightly, bubble chamber research has been superseded, there is still cloud chamber research continuing, not least at CERN. Thanks to an introduction from Alan Watson, Professor of Physics at Leeds University, I was able to make contact with the leader of the cloud chamber project at CERN, Jasper Kirkby. One of the purposes of the CERN project is to discover if cosmic rays can actually be a causal factor in the formation of clouds in Earth’s atmosphere. Fascinating stuff. I thought Jasper Kirkby might be interested in the Wilson material that underpins this exhibition at HICA, and indeed he was. He sent a thoughtful response, which I to quote from here because it gives a very clear picture of the regard in which Wilson is held:

‘Wilson was a brilliant experimentalist. I am hugely impressed by the technical quality of his cloud chamber photographs. I doubt whether we could improve on them, even today. Yet he did all this with the laboratory glassware and materials (gelatin…) of 100 years ago. His cloud chambers look deceptively simple (I had a good look at them at the Cavendish a few years ago) but – like Harrison’s clocks – they were built by a virtuoso and were far ahead of their time.’

He concludes: ‘I think CTR Wilson would have been pleased to know that his cloud chamber concept is now the basis of the world’s leading experiment studying aerosol particles (cloud seeds) and clouds in the laboratory – exactly as he had envisaged when he originated his cloud chamber ideas at the Ben Nevis Observatory.’ [2]

So I do not want to give the impression that there is little appreciation of Wilson in the physics community, far from it. He just seems to have dropped out of public sight. This obscuring of Wilson from public gaze is the more ironic because the major history written about the experimental side of twentieth century particle physics devotes more space to Wilson than to almost anybody else. That history, Peter Galison’s Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics, published in 1997, extends to almost one thousand pages and consideration of Wilson’s apparatus is at the very heart of Galison’s text. Indeed Wilson has almost a full column of the index devoted to him.

Over the years I have often found myself teaching students about art and science, and about visual thinking as the great link between them, citing the work of Leonardo, Patrick Geddes, D’Arcy Thompson, C. H. Waddington, etc. But I would always try to put in a cloud chamber photograph or two by Wilson or by one of the scientists he enabled, not least because of the remarkable way his images, for example those from 1912, seemed to prefigure the experimental painting techniques of fifty years later. Such science-art connection can be misleading, but in the wider history of visual thinking these echoes between disciplines across time are at the very least interesting.

But that, and sticking the odd cloud chamber image to my office door was all that I managed to do until 2006 when I mentioned Wilson to Mervyn Rose, professor of physics and a colleague at the University of Dundee. He shared my interest and in due course added me to an email group, which was trying to get more recognition for Wilson by getting his face on a stamp or a bank note. Nothing came of that effort, but the contact with other people who cared about Wilson’s public profile was illuminating. One was Malcolm Longair, Jacksonian Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Cambridge, the current holder of the Chair that Wilson himself had held. Another was the above-mentioned Alan Watson. A turning point came at the end of 2012 when the Royal Society of Edinburgh marked the centenary of Wilson’s epoch-making 1912 paper with a one-day conference. I was able to meet people who had only been names to me on the email circulation list, including Malcolm Longair and Alan Watson whose presentations re-emphasised for me not only Wilson’s scientific value but also the aesthetic importance of that achievement.

By this time I could see an art/science project taking form around Wilson’s key early images. My initial thought was to find a set of good prints of those pioneering potographs. At that time one could only access them easily through the fairly greyish halftones typical of scientific publications circa 1912. Even in that form they are beautiful, but I wanted to raise the visual level on which they could be appreciated. I thought that would be straightforward enough, so with the help of Joanna McManus, the image librarian at the Royal Society in London I inspected the original paper in the proceedings and began to study associated material. That associated material included a wonderful selection of Wilson’s images made by Philip Dee, Wilson’s student. Dee became Professor of Physics at Glasgow, and was, like Wilson a Fellow of the Royal Society. But I could find no set of prints or negatives corresponding to the 1912 paper. However two other things were happening by then. Alan Watson (himself a Fellow of the Royal Society) and I were in contact and supporting each other in our various efforts, in particular with respect to attempting to get Wilson represented in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and having his images given prominence in the redevelopment of the physics display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. In addition I had been in touch with another of the speakers at the Royal Society of Edinburgh conference, Andrew Wilson, C. T. R. Wilson’s grandson. Andrew told me that he some material, which I was welcome to have a look at. That was an intriguing offer. Thanks to the support of the Royal Society of Edinburgh I was able to cover travel costs to pursue things further. My expectation was that I would also visit the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge, where Wilson had been professor. In fact I never got there. The reason I did not get there is the basis of the exhibition that took place at HICA, namely the material that Andrew Wilson had in his possession. In summer 2014 Andrew showed me a few boxes on glass plates, which looked distinctly intriguing, which he suggested I took away to examine at my leisure. I was only too pleased to do so. His only stipulation was that I should try and find a good collection to which he could present the work. I did so, and the greater part of that collection has now been accessioned by the Royal Scottish Academy.[3]

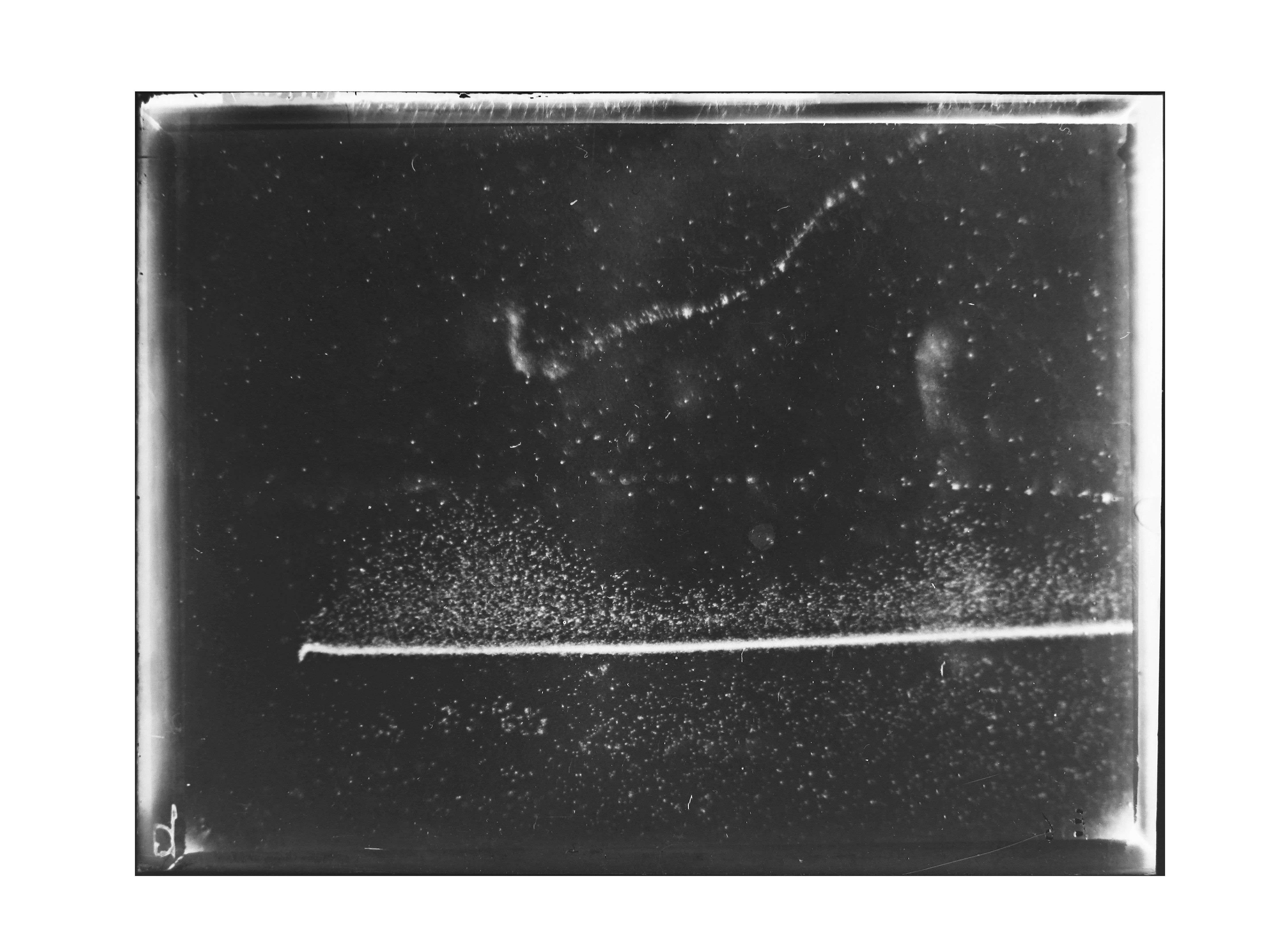

The original glass plate negative of one of the images in Wilson’s 1912 paper

The image in positive form

The image in positive form

And as it appears in Wilson’s 1912 paper

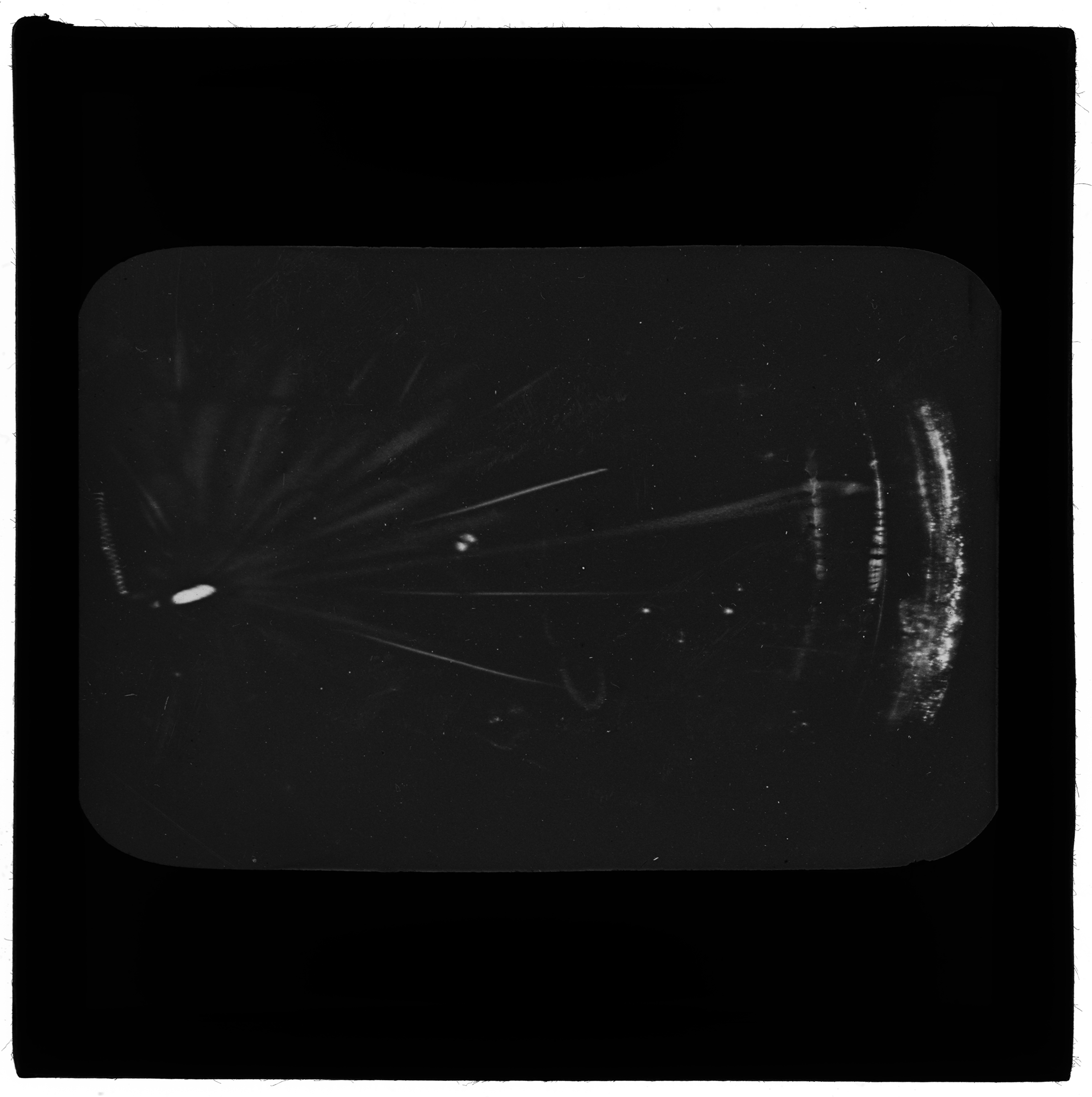

When I began to examine the collection it was utterly fascinating. There were about sixty items, a mixture of glass plate negatives, positive lanternslides and a few prints. It included a glass plate negative of one of the images in Wilson’s key 1912 paper, something I had been searching for. But one of the first things I noticed were lanternslides that showed the two images from Wilson’s 1911 paper. These are among the most important images in the history of science. They are the very first records of the tracks of sub-atomic particles. And I was holding Wilson’s own lantern slides in my hands.

Discovering the lantern slides

In due course they were digitized for me by my Dundee colleague Gair Dunlop, and printed at the Visual Research Centre of the University of Dundee by Paul Harrison. They were a key feature of the installation at HICA, both in themselves – shown at various scales – and as the basis of a number of my own photographic responses to Wilson’s work.

I realized that Andrew Wilson’s collection of his grandfather’s material was an important collection by any standard. Some elements of it are unique, for example a glass plate negative which is clearly the basis of one of the key images in Wilson’s 1912 paper for the transactions of the Royal Society. It was that negative which provided the stunningly beautiful positive image used on the HICA exhibition invitation card. However just as important as such unique material was material that gives insight into Wilson’s lectures and communication with colleagues, in the form of positive lantern slides of key images, such as the two images from the 1911 Royal Society paper that I have noted.

My intention is that the collection in its new home in the Royal Scottish Academy will act as a catalyst to draw attention to the significance of Wilson from the point of view of artists as well as from a scientific point of view. I hope it will help us recognize Wilson’s role as a pioneering photographer, and as such of importance as part of the history of photography, as well as a pioneering scientist. Finally I would like that gift from Andrew Wilson to act as focus to encourage study of other Scottish collections of Wilson’s work (and indeed collections elsewhere), for example those of Glasgow, Aberdeen and Heriot Watt universities.

In conclusion I want to explore Wilson’s aesthetic through his own words. When he was awarded his Nobel Prize in 1927, he began his speech as follows:

‘In September 1894 I spent a few weeks in the Observatory which then existed on the summit of Ben Nevis, the highest of the Scottish hills. The wonderful optical phenomena shown when the sun shone on the clouds surrounding the hill-top, and especially the coloured rings surrounding the sun (coronas) or surrounding the shadow cast by the hill-top or observer on mist or cloud (glories), greatly excited my interest and made me wish to imitate them in the laboratory.’

That attempt to imitate those conditions in the laboratory laid the basis for Wilson’s cloud chamber. But as he himself says: ‘my experimental work on condensation phenomena was not resumed for many years’ until ‘towards 1910 I began to make experiments with a view to increasing the usefulness of the condensation method.’

And then he describes the extraordinary moment when he saw the tracks of elementary particles for the first time:

‘Much time was spent in making tests of the most suitable form of expansion apparatus and in finding an efficient means of instantaneous illumination of the cloud particles for the purpose of photographing them. In the spring of 1911 tests were still incomplete, but it occurred to me one day to try whether some indication of the tracks might not be made visible with the rough apparatus already constructed.

Wilson’s lantern slide of his first successful cloud chamber image

The first test was made with X-rays, with little expectation of success, and in making an expansion of the proper magnitude for condensation on the ions while the air was exposed to the rays I was delighted to see the cloud chamber filled with little wisps and threads of clouds – the tracks of the electrons ejected by the action of the rays.’

Wilson’s lantern slide of his second successful cloud chamber image

‘The radium-tipped metal tongue of a spintharoscope was then placed inside the cloud chamber and the very beautiful sight of the clouds condensed along the tracks of the Alpha-particles was seen for the first time. The long thread-like tracks of fast Beta particles were also seen when a suitable source was brought near the cloud chamber.’

‘Some rough photographs were obtained and were included in a short communication to the Royal Society made in April 1911.’

The images as they appear in Wilson’s 1911 paper

I repeat: ‘Some rough photographs were obtained.’ That is a bit like Galileo saying that he had obtained some rough drawings of the moons of Jupiter whilst looking though his telescope in Padua in 1610. I have already noted these two ‘rough photographs’ that Wilson published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society in 1911. They are among the most important images in the history of science. They are the very first visualizing of Alpha and Beta particles.

Wilson’s pleasure in the visual is evident: listen to what he says of the first photograph:

‘I was delighted to see the cloud chamber filled with little wisps and threads of clouds – the tracks of the electrons ejected by the action of the rays.’

And of the second:

‘the very beautiful sight of the clouds condensed along the tracks of the Alpha-particles was seen for the first time.’

However rough these images were by Wilson’s later standards, it is clear that they were to his mind also very beautiful. Words like ‘beauty’ and ‘delight’ – aesthetic words – characterize Wilson’s approach to nature, to science and to his own images.

My aim in this brief reflection has been to give some insight into the beauty and delight that Wilson felt, and conveyed to others through his photography.

Some of Wilson’s images as installed at HICA

Some of Wilson’s images as installed at HICA

A concluding note: After the exhibition at HICA in 2015 I gained further insight into Wilson’s image making. It was clear to me that a number of his published images were enlarged details rather than images made from the complete plates. To make a suitable image for display in the Royal Museum of Scotland I made such a detail from one of Wilson’s images.

My sampling of a Wilson negative showing the tracks of electrons ejected as a result of the action X rays.

That was particularly interesting to me from the perspective of this paper for a ‘good’ detail is, of course, an aesthetically pleasing detail and all such samples published by Wilson fall into that category. In September 2016 images from the RSA Wilson collection played a key part in the exhibition In the Belly of the Whale at Witte de With, Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam. In 2017 images from the collection were used to great effect by the artist Linarejos Moreno in Madrid at Alcobendas Contemporary Art Centre. A selection of the glass plates were displayed in the Ages of Wonder exhibition, at the Royal Scottish Academy in 2018.

Acknowledgments: On the research side particular thanks are due to Andrew Wilson and to Alan Watson; with respect to exhibiting the work my warmest thanks to Geoff Lucas and Eilidh Crumlish of HICA.

References and further reading:

Barrow, John. Cosmic Imagery: Key Images in the History of Science. London: Bodley Head, 2008

Capra, Fritjof. The Tao of Physics. Boulder: Shambala, 1975.

Dirac, P. A. M. ‘The evolution of the physicists view of nature.’ Scientific American, 208:45-53, 1963.

Dirac, P. A. M. ‘The excellence of Einstein’s theory of gravitation.’ In Einstein: The First Hundred Years. Edited by Maurice Goldsmith, Alan Mackay and James Woudhuysen. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1980.

Dirac, P. A. M. ‘The Test of Einstein.’ In Stuart Brown. Conceptions of Inquiry. London: Routledge, 1981.

Galison, Peter. Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Genter, W., H. Maier-Leibnitz and W. Bothe. An Atlas of Typical Expansion Chamber Photographs, Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1954.

Kaufmann, William J. Relativity and Cosmology. New York: Harper & Row, 1977.

Macdonald, Murdo. ‘Birth Order, Art and Science: a Study of Ways of Thinking.’ PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 1986.

Waddington, C. H. Behind Appearance: A Study of the Relations between Painting and the Natural Sciences in This Century. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1969.

Wilson, C. T. R. ‘On a Method of Making Visible the Paths of Ionising Particles through a Gas.’ Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1911 85, 285-288.

Wilson, C. T. R. ‘On an Expansion Apparatus for Making Visible the

Tracks of Ionising Particles in Gases and Some Results Obtained by Its Use.’ Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1912 87, 277-292.

Wilson, C. T. R. ‘On the cloud method of making visible ions and the tracks of ionizing particles.’ Nobel Lecture, December 12, 1927.

[1] Given on Saturday 25 July 2015. Alan Walker’s talk was followed by an event organised by the Royal Meteorological Society and Institute of Physics in Scotland (with the help of the University of Glasgow) in which participants successfully built their own cloud chambers from simple materials in order to observe the tracks of cosmic rays.

[2] Personal communication.

[3] As of 8 July 2016 two images sourced in that material are now on prominent display in the new science and discovery galleries at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.