Art, Maps and Books: Visualising and Re-visualising the Highlands

Plenary Address: Lie of the Land Conference, University of Stirling, 26-30 July 2006.

Murdo Macdonald, Professor of History of Scottish Art, University of Dundee.

What I want to do here is to bring together an art-historical account with other aspects of visualising the Highlands, but always returning to art as my core discourse. This not least with respect to contemporary developments such as An Leabhar Mor / The Great Book of Gaelic, which was published in 2002 and is a clear example of reappropriation of contemporary visual art from the perspective of the Gaidhealtachd.

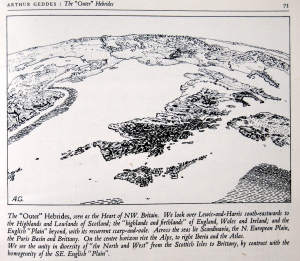

The first image I want to consider, my keynote image if you like, is a map. This map takes the Highland point of view. It is a drawing by the geographer Arthur Geddes and it was published in 1948 to accompany his seminal paper, The ‘Outer’ Hebrides, a paper in which he redefines centre and periphery by the simple device of adding quotation marks to the word ‘outer’. In this paper he takes on board the ideas of his father Patrick Geddes, and his father’s friend the French anarchist geographer, Elisee Reclus. This is a visualising of the Highlands in European terms and Europe in Highland terms.[1] At the same time, both Scotland and Europe are seen as part of the globe itself, in an ecological vision extending from Scandinavia to Africa. If we fly across this map so to speak, one of the first places we come to is Ardroil in Lewis where the famous Lewis chess pieces were found. Instead of seeing Lewis from a metropolitan point of view as a strange peripheral place, Arthur Geddes’ map allows us to see it at the heart of medieval European trade routes, and chess pieces in this location in the middle of the twelfth century begin to make considerable sense. The more so when we observe that although these pieces were probably made in Norway, as we can see from the side details on several of the thrones, aspects of the decoration are distinctly Celtic. Perhaps these works were en route to the retinue of the Lord of the Isles, perhaps they were en route to the Mediterranean. Whatever the story the decoration reflects the interplay of Norse and Celtic cultures which defined so much of Scotland and Ireland of the period.

Another of the places we come to early on with Arthur Geddes’ viewpoint as our guide is Calanais. Ten miles or so from Ardroil, its standing stones are indicative of another, much earlier culture, dating from four or five thousand years ago. There is so much to say about this Lewis archaeological site and its associated stone circles that I will not even start, except to mention its profound effect on contemporary artists, of which more in due course. Carrying on south from Calanais one comes to Balallan in the district of Lochs and there one encounters a different cultural situation again, namely the late nineteenth century clash between absentee landlords and indigenous people. Just outside Balallan is the site of a major community sponsored memorial designed by the artist Will Maclean and built in 1994. It is one of a set of three memorials commissioned to mark different phases of the struggle for land in Lewis from the 1860s to the 1920s.[2] But Maclean’s project marks more than that for it is part of the sustained activity in visual art, literature and drama that was one of the driving forces of political devolution for Scotland.

Tracking across the Minch to Skye we find the inspiration of another work by Will Maclean which brings more Highland issues into focus. Made in 1984 it is a construction measuring about 18 inches across. It shows the boarded up window of a deserted croft. Looking out through this window we see the conning tower of a submarine. In this work Maclean draws together two essential and interconnected elements of our visualisation and revisualisation of the Highlands and the Gaidhealtachd: clearance and militarism. The title of this piece is Inner Sound, and this gives us a specific geographical location for the work. The ‘Inner Sound’ in question is the stretch of water between Raasay and Applecross, with which in his days as a fisherman Maclean was very familiar. But there is a hint also of a psychological inner sound that we should be listening for. This sound is the sound of the Gaelic language. To some of us it is the sound of a language we still understand. To others, including myself, it the sound of a language which we should understand, but which we have lost. A language that has been culturally cleared from us. So there is another layer to Maclean’s reference to clearance here for loss of land is often the loss of language as well, and – as his work implies – the trade-off of a language for weapons systems is not a good one, anymore than was the trading-off of that language for sheep or deer.

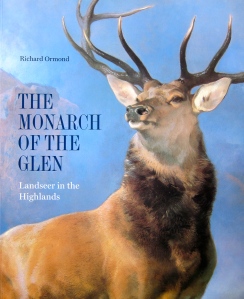

The locating of this work in Raasay gives us another clue as to how we should read it, for this boarded window is a deliberate link to Sorley MacLean, himself the subject of a notable portrait by Alexander Moffat. Will Maclean’s reference in Inner Sound is to lines of the poem Hallaig which read, in poet’s own translation from the Gaelic: ‘The window is nailed and boarded / through which I saw the West’. We stand at a point in our history today that gives us an opportunity to unboard that window. Part of that process of repair must, I think, involve understanding visualisations and revisualisations of the Highlands. Maclean’s image also helps us to understand the parameters within which were made stereotypical images of the Highlands such as Landseer’s Monarch of the Glen. Where Landseer’s deer (and the estate surrounding it) existed to serve the pleasure in hunting of people who did not even need to eat it, Maclean’s window is symbolic of all those windows which once sheltered people who needed to eat deer that were denied to them. There is a grand disjunction here between those who hunted deer but did not need to and those who would have liked to hunt deer to sustain them and their families, but were prevented from doing so. In 1887, thirty-six years after Landseer painted the Monarch of the Glen, this tension was sharply expressed in Lewis, when the men of Pairc put their own human rights before the legal rights of the estate owners and hunted the deer. It is that great deer raid of November 1887 which is commemorated by Will Maclean’s memorial outside Balallan in Lewis.

In another window reference Maclean addresses the closely associated theme of emigration. The window is not Sorley MacLean’s window that is nailed and boarded, but a window that is if anything even more evocative of loss of people and culture, namely the east window of Croick Church in Sutherland. On this window the evicted tenants of Glencalvie, taking refuge in the churchyard in May 1845, scratched messages of despair. In his work, entitled Emigrant Ship, Maclean brings the Croick window image together with a graffiti image of an emigrant ship scratched on the wall of a deserted schoolhouse in a cleared settlement in Mull. But reflected in the window is another emigrant ship, this one firmly embedded not only in Highland history but in the history of Scottish art, for it derives from a series of emigrant ship paintings made by William McTaggart in the 1890s. Thus Maclean invokes the history of Scottish art in his exploration of Scottish historical and contemporary issues. It is to this history that I now turn.

The best known of William McTaggart’s works on the theme of emigration is The Sailing of the Emigrant Ship painted in 1895, and now in the National Gallery of Scotland. It looks back to McTaggart’s own experience of emigration from the communities he knew in Kintyre during his childhood. McTaggart was not only the artist who opened up the possibilities of modern art for other Scottish artists, he was also a Gaelic speaker. This opens up another perspective on how art relates to the Highlands. Although in terms of training modern art is predominantly a metropolitan product, nevertheless the modern art of Scotland is firmly driven by the work of a man rooted in – and continuously returning to – the Gaidhealtachd. McTaggart’s art is defined by this relationship throughout his career. Particularly illuminating are three paintings he made in the 1890s. Along with The Sailing of the Emigrant Ship, McTaggart painted The Coming of St Columba and The Storm. Between them these three paintings reflect Highland history from the early days of Christianity to the threat to communities posed by emigration. In a sense the heart of the three paintings is The Storm. It is both an experimental work of 1890s art and a reflection of the dangerous realities of life in the coastal communities of Kintyre, in this instance Carradale.[3]

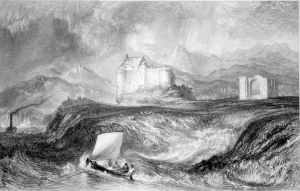

J. D. Fergusson once wrote that no artist had ever painted the sea better than McTaggart, and McTaggart shows us that in any complete visualisation of the Highlands the sea and those who work the sea must play a large part.[4] Again this gives a much needed context to stereotypical Monarch of the Glen type imagery. Landseer was, of course, English but I should stress that it is not my intention to criticise artists on the basis that their views have a cultural starting point external to the Highlands. The fact is that many highly interesting perceptions of the Highlands have come from artists from south of Border. Notable here is J. M. W. Turner, not only the greatest English artist of his day, but a painter with a real claim to be the greatest European artist of his day. Since we normally think of Landseer in conjunction with Sir Walter Scott, despite the fact that The Monarch of the Glen was not painted until twenty years after Scott’s death, it is something of a paradox that we neglect the imagery of Turner, for he worked extensively with Scott, responding to Scott’s works as they relate both to Scotland and to Europe. But then, Turner produces thoughtful, experimental works, not easy to use as stereotypes. These works were created as frontispieces and title page vignettes for Scott’s poetical and prose works and they were presented as steel engravings, often engraved by the outstanding Edinburgh engraver William Miller.[5] They were therefore among the most common and widely distributed images of the Highlands from the 1830s onwards. Many of them, such as Dunstaffnage, honour the sea in way worthy of McTaggart half a century later.

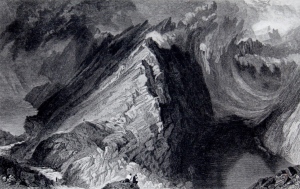

At the same time, as for example in Loch Coriskin (i.e. Loch Coruisk) Turner creates a suggestive exploration of the geology of the Highlands. Ruskin called this type of approach Turnerian topography, that is to say an often exaggerated view which nevertheless corresponds in some way to scientific reality on the one hand and to the emotional charge of the place on the other.

Such commitment to geology was taken up by Scottish artists of the next generation, for example, despite a massive shift in scale, Turner’s Loch Katrine was almost certainly an influence on Horatio McCulloch’s version painted some thirty years later. McCulloch is often thought of today as a Victorian painter of interest primarily as someone for the founders of modern art in Scotland to react against. It is certainly true that McCulloch represented a style which younger artists were determined to move on from, however, we must take care not to let that obscure his abilities and interests. For example, if any artist explores the geology of the Scottish Highlands in detail it is McCulloch. If, instead of thinking his work under the heading of ‘romantic landscape’ we think of it under the heading of ‘geological essay’, we can read it differently. Coincidentally one of the great geological maps of Scotland was created by another McCulloch, John Macculloch, whose images of the Highlands both in plan and section are an extraordinary achievement. Macculloch’s map was published in 1836 just as Horatio McCulloch was beginning his career as a painter. Scotland had been at the heart of the development of the science of geology from the late eighteenth century onwards, and the first half of the nineteenth century was a time of considerable geological controversy. The debates themselves are not my concern here, what is my concern is that the geology of Scotland was a major topic of discussion throughout the scientific world at the time. John Macculloch’s map is a key part of this and we should see Horatio McCulloch’s paintings in relation to that current of geological thinking.[6]

So that is a broader context for images like The Cuillins from Ord which McCulloch painted in 1854. It is a well observed image, admittedly with a nod to the exaggerations of Turnerian topography, but relatively accurate nevertheless. It is informative to compare such work to photographs of the Cuillins. An example is a view of Sgur nan Gillean which appears in James Geikie’s Mountains: Their Origin, Growth and Decay, published in 1913. Despite its ostensible scientific purpose this photograph is every bit as consciously expressive of the drama of landscape as is a painting by McCulloch. It is part of what was by then a growing body of photography of the Scottish mountains which had earlier exponents such as George Washington Wilson and develops into the powerful, aesthetically balanced images of Robert Moyes Adam in the 1920s and 1930s. A major source of the high quality photographic imagery from the 1920s onwards is the series of guidebooks published by the Scottish Mountaineering Club. The interesting point is that the approach to mountain images often has as much an aesthetic as a guiding function, for example W.A. Mounsey’s view of the Cuillin ridge from the Skye guide of 1931 which is clearly included for its aesthetic value rather than for the climbing information it provides.[7] These guides have good design and production values and often include fold-out maps by John Bartholomew of Edinburgh, indeed the work of that map-maker is another of the high points of Scottish visual culture of the early decades of the twentieth century. There is a sensitivity to colour and line in these maps whether they appear in humble pocket touring atlases from the 1920s – where a feature like Glencoe is only about an inch long but still highly legible – or as part of major academic research projects for example giving visual form to Sir John Murray’s comprehensive Bathymetric Survey of Scottish lochs which appeared in The Scottish Geographical Magazine from 1901 onwards.

But to return to Horatio McCulloch. Consider his work Storm on a Highland Coast painted in 1855, which again shows Skye with Blaven in the distance. McCulloch painted this area of southern Skye a number of times, not simply for its visual potential, but also because he had family connections there. His wife, Marcella Maclennan came from Sleat, and when this is noted one finds McCulloch far closer to the issues of the Gaidhealtachd than one might initially suppose. McCulloch was not a Gaelic speaker himself, but his wife probably was. I do not know what his views (or those of his wife, who may well have come from a landed family) were on clearance and emigration, but he recognised the emigrant’s nostalgia for Scotland in a remarkable painting of imaginary mountain and loch scenery The Emigrant’s Dream of his Highland Home.[8] This leads me to comment that even in the iconic image Glencoe from 1864 McCulloch includes a road when he could have easily concealed it, so he was not in the game of creating false visual wilderness. Glencoe may be a wild landscape of exposed geological features but McCulloch makes clear to us that it is not an uninhabited one. Deer and people exist in the same space. This is interesting if we think of McCulloch’s family links with the Gaidhealtachd and if we bear in mind that one of the great Scottish poetical appreciations of both deer and landscape is Duncan Ban MacIntyre’s Gaelic poem In Praise of Ben Dorain. So perhaps when we look at deer in work by McCulloch, if we are looking for a literary resonance we should be looking to Duncan Ban MacIntyre as much as to Sir Walter Scott. That is, of course, speculative, but one of my aims here is to develop and explore perspectives which allow us to reconsider works which we have perhaps taken for granted.

It should be noted that when McCulloch was painting in southern Skye in the 1850s, a major clearance of people in favour of sheep had just taken place in Suishnish at the behest of the administrators of Lord Macdonald’s estate. In the most well known account of this clearance geology again plays a part, for it is to be found in Archibald Geikie’s Scottish Reminiscences. Archibald was the elder brother of James Geikie and the first holder of the Murchison chair of Geology at Edinburgh University. He spent considerable periods analysing and recording the geology of Skye, and it was during one of these field trips – probably in 1852 or 1853 – that he encountered this clearance. It is a harrowing account which begins with Geikie recording how he could hear the wailing of the people before he could see them, and then: ‘On gaining the top of one of the hills on the south side of the valley, I could see a long and motley procession winding along the road that led north from Suishnish.’ He concludes with the words: ‘I have often wandered since then over the solitary ground of Suishnish. Not a soul is to be seen there now, but the greener patches of field and the crumbling walls mark where an active and happy community once lived.’[9] Geikie then proceeds to describe the effect of clearance on Raasay and we find ourselves back with Sorley Maclean at Hallaig looking out through a window that is nailed and boarded. Such accounts of clearance underpin one of the first successful uses of art and wider imagery to explore the history of the Highlands.

This took the form of an exhibition at An Lantair Gallery in Stornoway in 1986.[10] There the stereotype of the Highlands as a massive sheep farm or sporting estate was a starting point for critique. The exhibition was a major step in the re-appropriation of visual art from the perspective of the Gaidhealtachd. It was entitled As an Fhearann / From the Land with the subtitle ‘Clearance, Conflict and Crofting’ and the visual material was given historical context in a supporting catalogue in both Gaelic and English. It was followed in 1989 by another highly significant exhibition Togail Tir / Marking Time: The Map of the Western Isles, which provided a cartographic underpinning for the whole visual-cultural debate. The same year saw a reassessment of the work of William McTaggart in a major exhibition mounted by the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh.

These exhibitions would seem to have laid to rest the Landseer-type stereotype of the Highlands. What is wrong with such stereotypes is not that they exist (indeed they always correspond to some aspect of reality) but that they fail to reflect the plural nature of any culture. Such stereotyping is a method of concealing cultural realities, but at the same time creating a powerful imagery that seems to reflect that culture. It promotes what Frantz Fanon called ‘inferiorism’ that is to say adopting an image of one’s own culture which is mediated by a colonial power, and which overvalues the culture of the colonist and undervalues the culture of the colonised. Whether one can adopt this precise terminology in the case of Scotland is a moot point, however the power relations reflected by the imagery are the same. It is, therefore, to say the least an irony that the first exhibition to deal with Scottish material to be mounted by the National Galleries of Scotland at the newly refurbished Royal Scottish Academy building in 2005 was devoted to Landseer and the Highlands. What was ‘baffling and worrying’ – and I adopt those words from Moira Jeffrey’s review in The Herald – was the uncritical context in which the exhibition was mounted. Jeffrey noted that the exhibition was ‘interesting evidence of the way cultural colonialism is inevitably absorbed, internalised and celebrated by its own subjects.’[11] Quite so. The Sunday Herald critic, Catriona Black, herself a Gaelic speaker, summed it up for many by pointing out that the National Galleries of Scotland seemed to be at home with what she described as a ‘pernicious Victorian attitude’ to the Highlands and Highlanders and they were, she continued, ‘unbelievably in this day and age … happy to promote it.’[12] Even the most positive reviewer of the exhibition north of the Border, Iain Gale in Scotland on Sunday, described The Monarch of the Glen as a ‘well-intentioned, if patronizing visual metaphor for the Highlands and its people.’[13]

At a time when a start had been made by the Scottish Parliament on long overdue land reform surely this exhibition should have been an opportunity to explore rather than reinforce that patronizing visual metaphor? In The Scotsman, Duncan Macmillan called the exhibition ‘the ghost of the redundant iconography of an imaginary Scotland’.[14] But he also pointed out that had Landseer been given proper context there could have been much more worth in the exhibition. Indeed exploring Landseer in terms of Victorian repressions, fantasies and imperial dreams would have been interesting, but that did not happen. ‘Disturbing and worrying’ it certainly was. It was as though As an Fhearann had never existed. Instead, the Landseer exhibition left one hermetically sealed in the world parodied in 1973 by John McGrath in The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black, Black Oil. At one point McGrath puts the following lines into the mouths of Lord Crask and Lady Phosphate as they sing: ‘And if the locals should complain / Well we can clear them off again.’[15]

But it is harder to clear people now. The law has changed for the better, let us hope that the mindset of the National Galleries of Scotland will follow suit, under its new director.

To be fair, the education department of the gallery did its best to provide context, not least by inviting the contemporary artist Ross Sinclair to give a presentation. Sinclair has shown consistent interest in both stereotypes and folk tradition in his work. His ‘Highland Clearances’ T shirt was made in 1998 as part of another An Lantair exhibition, MacTotem. That exhibition was a series of proposals for new and not always polite uses for that symbol of clearance and emigration, the Duke of Sutherland monument above Golspie. Perhaps we should not be surprised to find Landseer painting the Sutherland seat of Dunrobin Castle in 1835, that is to say at precisely the time this monument was being planned and built. Landseer was a man of his time, a sporting artist who painted hunted animals, the estate owners who hunted them and the Highlanders who served those estate owners. As such he has his interest, not least for historians. But to repeat the point: this exhibition was the first to deal with Scottish material to be mounted by the National Galleries of Scotland at the newly refurbished Royal Scottish Academy building. As such it should have marked a new beginning. It did not.

Had those same resources been devoted to McCulloch’s place in the visual culture of Scotland, I wonder what might have come of it? As I have noted, we pay so little attention to McCulloch that it is easy to think of him as a painter of deserted landscapes but in fact – along with geology – human habitation is an important part of his compositions. For all its ruined castle and majestic scenery, The Emigrant’s Dream of his Highland Home is dotted with distant boats, buildings and the smoke of domestic fires. The traces of people may be unobtrusive, but that is because they are in scale with the landscape, not because they are not there. The emigrant’s dream is not of a sublime wilderness, but of a place of natural beauty and sufficient resources for people to live. One might argue that McCulloch’s image is of the kind of idealized Highland place referred to by Alexander Carmichael in his notes to a version of the tale of Deirdre, which he collected in Barra in 1867. Carmichael writes of Deirdre’s bower at Dalness in Glen Etive as a place where ‘the deer of the hill could be shot from the window and the salmon of the stream fished from the door’ and continues ‘The spot is most beautiful and the prospect most magnificent.’[16] When this similarly ‘magnificent prospect’ by McCulloch was engraved it emerged with a new title, My Heart’s in the Highlands. Not a major change in sentiment, perhaps, but consider now that the image is being presented as an appropriate accompaniment to Robert Burns’ song of the same title. This is an important reminder of Burns’ contribution to our visualizing of the Highlands that can help again to put our perception of Scott’s contribution to Highland imagery into a wider context.

As one would expect from their age difference, landscape imagery related to Burns was being published before Scott even wrote about the Highlands. For example an engraving from 1805 by John Greig of his own drawing of the falls at Aberfeldy, refering directly to Burns’ famous song, or the same engraver’s image of a painting by Alexander Nasmyth of the Falls of Foyers, which Burns had visited in 1787.[17]

This latter work has the added interest that it draws our attention to the fact that Nasmyth was not only Burns’ friend and portraitist but was also one of the first to illustrate his work through landscape rather than through genre. It should also be remembered that – far more overtly than Scott – Burns was an admirer of James Macpherson’s Ossian, and his interest in Highland landscape and culture should certainly be seen in that light.[18] Macpherson provides yet another perspective on the Highlands and Highlanders, both from the point of view of eighteenth and nineteenth century art and in terms of the art of today. Crucial here are Alexander Runciman’s images from the late eighteenth century. One of these forms the basis of a twenty-first century work, Calum Colvin’s series of images Ossian: Fragments of Ancient Poetry, first shown at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in 2002. A more recent showing was at UNESCO in Paris in 2005 and the Paris link reflects the interest in Ossian among writers and artists in continental Europe at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Indeed at the time Colvin’s work was on show in Paris there was a major exhibition of one of those artists, Girodet, at the Louvre. At the heart of that exhibition were Girodet’s extraordinary Ossian works.

Balancing his role in European art, Macpherson’s influence on Highland imagery is very clear, not least in works such as John Miller’s depiction of Fingal’s Cave used to illustrate Thomas Pennant’s A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides published in 1776. Turner also figures here for one of the most influential of his works of the 1830s is Staffa, Fingal’s Cave painted in 1832. It is one of his most subtle and evocative seascapes: in it the presence of the island and the cave are almost felt rather than seen. Turner is well known for his exploration of the interplay of the power of the weather and the forces of industry, in particular steam power. This painting is a fine example of this aspect of his work, and it reminds one that he also took an interest in a major engineering intervention in the Highlands, namely Thomas Telford’s Caledonian Canal, of which he made a painting. Over a century later one finds even greater engineering interventions in the Highlands in the network of hydroelectric dams, tunnels and generating stations developed in the years after the Second World War. These are of considerable visual interest in their own right and although I do not have the opportunity to do them justice here, I can at least note the perhaps unexpected ‘romantic landscape’ approach to photography related to the schemes when they were commissioned, for example a photograph of Ben Lomond from inside one of the Loch Sloy tunnels.[19] While these massive but well-established projects arouse relatively little controversy today, the same cannot be said for the new breed of renewable generation, wind-power. From the point of view of art it is interesting to note that work displayed on billboards by Matthew Dalziel and Louise Scullion in 2005, under the title Breathtaking, functioned very much as art should, namely as a site for thinking. When I asked Matthew Dalziel how the work had gone down with those who had seen it he made an interesting comment. He got the impression that those who were opposed to wind-power interpreted the images as supportive of wind-power, while those in favour of wind-power interpreted the images as critical of wind-power. In short the images – regardless of one’s starting position – were acting as ways of interrogating one’s own feelings and prejudices, and if anything is the sign of a good work of art it is that. The underlying issues with wind power and indeed hydroelectric power are design, planning and, crucially, ownership. Who owns the Highlands? Too often, the Highlands are still in the grip either of hard to identify owners hidden behind offshore companies or of the ministry of defence. How can a local community have a real stake in decision making, for or against anything, in those circumstances? The introduction of community ownership legislation is beginning to change this situation but the problem is larger than simply shifting land from absentees to locals. For example, would Westminster politicians be so keen to advocate a new generation of nuclear weapons, if they could not dump them up a sea loch in the Highlands? I doubt it. There is a wider history here, for the Highlands have hosted arms dumps and testing grounds since the eighteenth century. The pernicious trade-off between culture and militarism that Will Maclean draws attention to in Inner Sound is as acute now as it ever was.

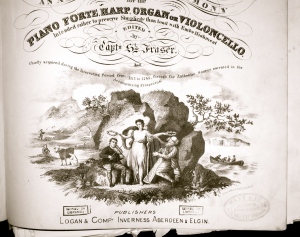

Perhaps I am digressing a little from Ossian here. Then again, perhaps not, because James Macpherson’s driving force was the destruction of the Gaelic culture of which he was part in the aftermath of Culloden, that is to say in the aftermath of the battle that firmly maintained the notion of the Highlands as a military zone. Whatever the ironies attached to Macpherson, his greatness lay in his ability to defend Highland culture by making it widely acceptable in a period when it was under great pressure. The effect of his work can be seen in nineteenth century uses of Ossianic imagery, for example, one finds a notable combination of Ossian and landscape on the title page of Simon Fraser’s Airs and Melodies of the Highlands and the Isles of Scotland, published in 1816.

Ossian appears with Fingal’s Cave in the background, but the link is also made directly to Niel Gow, the great eighteenth century fiddler and composer, who appears with the central Highlands as his backdrop. Note that, in this image, both Ossian and Gow are valued equally by the muse. Niel Gow’s features had been a symbol of Scottish folk virtues from the images by David Allan in the 1780s, through Raeburn’s portrait in the 1790s to David Wilkie’s Penny Wedding in the second decade of the nineteenth century. He lived not far from the waterfall now overlooked by Ossian’s Hall near Dunkeld, which is today more often referred to as the Hermitage. There is some suggestion that Macpherson himself may have advised the fourth Duke of Atholl on the project in 1783.[20] Who knows, Gow may have provided the evening’s entertainment. But there is another Ossianic monument near Dunkeld. Clach Ossian is a prehistoric standing stone on the way to Crieff, and local legend identifies it as the grave of Ossian. It has a particularly interesting history. In 1732 it was shifted by military road makers, revealing ancient remains beneath. One can see the route of this road on General Roy’s map of the Sma’ Glen, which dates from about 1750. Notwithstanding the neolithic or bronze age date of the uncovered remains, from the point of view of the traditional culture of the local inhabitants, this was indeed the grave of Ossian.[21] When the remains were disturbed the community removed them to a safer spot high above the road. This spectacle of remaking Ossian’s grave in the context of anti-Jacobite military road-making activity, finds a curious parallel in James Macpherson’s own remaking of Ossian’s poetry a generation later.

Clach Ossian brings me to consider an issue I touched on at the beginning of this paper, namely the significance of such ancient sites for artists working today. A manifesto of this movement was Lucy Lippard’s book Overlay, published in 1983, which has the subtitle ‘contemporary art and the art of prehistory’. Scottish prehistoric sites get considerable attention from Lippard, not only standing stones but carved rock surfaces such as those at Achnabreck near Crinan, one of the largest of any concentration of cup and ring marks. These works have been resonant in form for Scottish artists working today, for example Elizabeth Ogilvie’s collaboration with Donald Addison in 2002 to illuminate a line of poetry from the seventeenth century poet Mary Macleod. The line focussed on [‘Ri fuaim a taibh’] is translated as ‘at the ocean’s sound’ or perhaps ‘at one with the sound of the ocean’. Ogilvie’s water-derived work certainly evokes that but at the same time the formal echo of rock art is an unmistakable context for this imagery. Again, Julie Brook working on Mingulay seems to refer back in her work to the simplicity of the simple cup mark, at the same time exploiting the extraordinary quality of Highland light. It is that quality of light that made possible some of the most significant works of the Scottish colourists in the early twentieth century, for example Caddell’s The North End, Iona painted in about 1914. And it is worth remembering how responsive to light the artists of prehistoric times were through their intelligent use of materials and their positioning of stones with respect to the sun. Consider for example the rich red hues evident in some light conditions in the standing stones of Machrie Moor on the island of Arran. This is land art on a grand scale that extends throughout the Highlands.

I want now to turn to the standing stones of Calanais. These have been particularly influential on contemporary artists. In 1995 a major exhibition of work responding to this prehistoric site was held at An Lantair in Stornoway. The contributions ranged from the sensitive realism of Frances Walker’s lithography to the minimalism of Alan Johnston’s painting. Other notable contributions came from, among many others, Jake Harvey, Fay Godwin, Will Maclean, Calum Angus Mackay and Eileen Lawrence. Like the publications accompanying As an Fhearann and Togail Tir the exhibition catalogue stands the test of time. It is a key part of the reappropriation of contemporary art for the Highlands. A further contribution was from Richard Demarco who used the exhibition as an opportunity to revisit his remarkable group journey through neolithic Europe from Malta to Orkney in 1976. Calanais was a key site on this journey, but one must also mention here the wider dimensions of Demarco’s Highland activity, in particular the inspiration he gave to Joseph Beuys with respect to his work on Rannoch Moor. The variety of responses to the Calanais stones ranged from attention to astronomical alignments to awareness of the peat in which the stones were once embedded.

An artist interested in both aspects is Norman Shaw: he writes of the relevance of ‘denudation and deposition’ and of ‘the interplay between organic and geometrical form’.[22] Shaw’s work can be seen as a visual exploration of these notions but at the same time these ideas can be applied to visualising the Highlands in general. For example, Horatio McCulloch’s paintings can be regarded as visual essays on such geological and botanical processes and the same can be said of Bartholomew’s maps. Shaw contributed not only to the Calanais exhibition but also to another key project, An Leabhar Mor /The Great Book of Gaelic. This is a book and exhibition of one hundred works, each of which involved the collaboration of an artist, a calligrapher and a poet. Elizabeth Ogilvie’s response to Mary Macleod, to which I have already referred, is part of it. The poetry ranged from that of anonymous medieval monks to contemporary poets such as Meg Bateman and Christopher Whyte. The artists and calligraphers worked together to make what is, if you like, a modern equivalent of an illuminated manuscript, informed by the values of contemporary art. For example, the artist Donald Urquhart worked with the calligrapher Louise Donaldson on the first verse of Sorley Maclean’s Hallaig, and again the window imagery comes through here. Will Maclean worked with the Irish calligrapher Frances Breen and with the poet Aonghas MacNeacail on MacNeacail’s poem reflecting on the arrival of St Columba in Scotland. In its English translation it is entitled ‘All that came in one coracle’ and this subject continues to be a key part of Maclean’s art not least in collaboration with Arthur Watson for a sculpture at Sabhal Mor Ostaig in Skye. Alastair Gray’s contribution was a typically witty remaking of a Celtic manuscript. He acted as both artist and calligrapher for an anonymous poem ‘My hand is weary with writing’ composed about 1100.

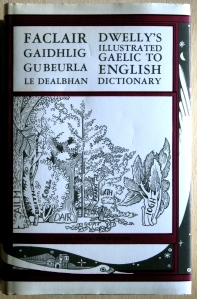

Mention of Gray moves my consideration on to another key book of the Highlands, namely Dwelly’s illustrated dictionary which was first issued in 1901, for Alasdair Gray did a cover for a new edition in 1977. This cover design is based on the Gaelic alphabet’s linkage of letter names and tree names, and this association has been explored by other artists, for example Graham Hardie. Edward Dwelly was an extraordinary person. He was an Englishman who immersed himself in Highland culture to such an extent that he became a prize-winning piper on occasion to the chagrin of home grown talent. But above all he was an outstanding linguist. His dictionary, which he printed himself in his studio as a kind of linguistic DIY project, is still a touchstone of Gaelic studies today. As a Gaelic learner himself he had a real insight into the problems of appreciating the subtleties of the language in terms of spelling and pronunciation shifts in different contexts. His decision to illustrate his dictionary, often with his own drawings, was inspired and on occasion one finds what are effectively visual essays on plants and birds. As one might expect in a Highland context, there is also a section on boat parts that resonates not only with artists who I have already mentioned, but also with little appreciated figures from Dwelly’s own time such as the Stornoway artist Malcolm MacDonald, who helped Dwelly to illustrate the dictionary.[23] MacDonald later made his career in Canada and is certainly worthy of further research. This is a salutary reminder that there is a hidden history of Highland art still to be explored. For example, we are only beginning to appreciate self-taught artists like Angus Morrison (1872-1942) whose work, thanks to the efforts of Finlay Macleod and Mary Smith was given its first showing in July 2006 at An Lantair in Stornoway. Had Angus Morrison lived in St Ives like Alfred Wallis or in Donegal like James Dixon, one suspects that he would have been recognised long before now.[24] The Morrison family is a visually gifted one, for one of Angus Morrison’s relatives is the photographer Dan Morrison whose body of work has created a remarkable locally-originated context within which to situate the work of photographers of the Western Isles such as Robert Moyes Adam, Violet Banks, Werner Kissling and Paul Strand.[25] I cannot even begin to explore photography in detail here. Others whose work demands attention include Murdo Macleod, Sam Maynard, Gus Wylie, and Calum Angus Mackay.

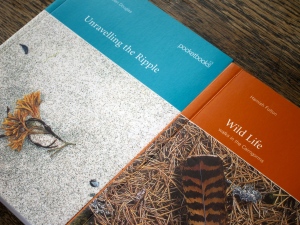

A contemporary artist whose work usually has a photographic aspect and resonates with Dwelly’s boat parts section, is the former Stornoway coastguard Ian Stephen. His work often takes the form of a visual essay balanced by poetry, for example his book Broad Bay, which is an ecological and cultural meditation on a place, a way of life, a method of construction and the forces which dictate the course of a boat. Looking at such clinker built boats reminds one that boats of this type of construction have been a subject for Highland artists for well over five hundred years. The West Highland galley is one of the earliest distinctly Highland representational subjects, and can be found in the carvings of the West Highland school of sculpture from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century. The work of this school is one of the major survivals of pre-Reformation art in Scotland. A key workshop for the school was Iona but examples can be found throughout the Western Isles and Western Highlands. This sculptural, heraldic treatment of the galley is a precursor of twentieth-century work, notably of William Crosbie’s cover for the first issue of Poetry Scotland in 1943. Crosbie here evokes the tale of the sea-rover Mac Iain Ghèarr ‘who harried the west coast of Scotland’ and ‘to avoid detection he had his ship painted white on one side and black on the other.’[26] This series of magazines was published by William Maclellan, whose other strongly visual publications include the magazine Scottish Art and Letters, George Bain’s remarkable visual analyses of Celtic art, Hugh MacDiarmid’s In Memoriam James Joyce illustrated by J. D. Fergusson, and, perhaps most important of all, Sorley MacLean’s Dain do Eimhir, again with images by William Crosbie. Maclellan is a hard act to follow as a publisher, but equally significant work has come in recent years from the editorial skill of Alec Finlay, whose folios and edited books – not least those in the Pocket Book series – have made a real contribution to visualising the Highlands and Islands.[27] Outstanding here is Unravelling the Ripple by Helen Douglas published in 2001. This visual essay is a complete contrast to the macro geology of McCulloch’s approach to landscape, it is instead in an intense and detailed view of a Hebridean tideline. Such intensity of view puts one in touch with art as part of what one individually engages with, rather than something that one surveys and represents from a distant perspective.

Another Pocket Book, Wild Life, takes this individual engagement further via the work of Hamish Fulton who records his walks in the Cairngorms in photographs and text. The use of imagery for aesthetic as well as route-finding reasons finds an interesting precursor in Scottish Mountaineering Club Guides and with Fulton the experience of hill walking itself becomes the art work. This notion of art as a walked experience has been developed by Angus Farquhar in a series of performances at key landscape points in the Highlands, most recently at Storr outside Portree. An outstanding example of Farquhar’s work was The Path in Glen Lyon in Perthshire in 2000. Among the musicians taking part was Martyn Bennett, who used the event to develop his extraordinary tribute to Gaelic singing, Glen Lyon: A Song Cycle.

There is a pilgrimage aspect to events like this. They may not be easy to get to and certainly in the case of The Path there was a powerful spiritual focus. In this sense they key right back into much earlier Highland art such as the great eighth-century crosses of Iona and Islay. When we begin to think of pilgrimage and the Highlands a whole other cultural mapping begins to emerge, although, as Patrick Geddes pointed out in 1920, the pilgrim and the tourist have a great deal in common, so perhaps this map is not as unfamiliar as it might seem.[28] In Highland terms the notion of pilgrimage does, however, focus us on one site in particular, namely Iona, and Iona also helps me to bring the diverse strands of this paper together, for many of the images I have referred to relate either to Iona or to Saint Columba. They have ranged from the West Highland school of sculpture, via the pioneering proto-modernism of McTaggart and Caddell’s radical colourism to Will Maclean’s work for An Leabhar Mor, but I have not even mentioned one of the most important of all Iona works of art. That is, of course, the Book of Kells. It was probably begun in Iona sometime around the year 800, and was later moved to Ireland as a result of Viking incursions. I take this not only as a suitable work to give conclusion to this paper on visualising and re-visualising the Highlands with respect to art, maps and books, but also as a work which can set us off again on tracks of international thinking, for like Arthur Geddes’ map with which I began, the Book of Kells is an utterly European document, indeed one of the high points of the European art of its day.

So let us unboard the window in Hallaig. Let us acknowledge the art of the Highlands both for its history and for its contemporary relevance.

Acknowledgement: This paper is made possible by an AHRC-funded project, Window to the West: Towards a redefinition of the visual within Gaelic Scotland. This is a collaboration between the School of Fine Art / Visual Research Centre at the University of Dundee and Sabhal Mor Ostaig in Skye.

[1] Arthur Geddes (1948) ‘The “Outer” Hebrides’, The New Naturalist , Summer, 1948, pp.72-76.

[2] The masonry in each case is the work of Jim Crawford.

[3] The narrative of the picture is a rescue boat being launched to help a fishing boat in distress.

[4] J. D. Fergusson (1943) Modern Scottish Art, Glasgow: Maclellan.

[5] For Cadell’s edition published in the early 1830s.

[6] Another artist and writer of relevance here is the strongly-geologically inclined John Ruskin, who spent a great deal of time exploring the Trossachs, often in the company of the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais. While I don’t think we should try to rethink McCulloch as a Pre-Raphaelite, many of the interests of recording of the natural world which underlie Pre-Raphaelitism underlie McCulloch’s attitudes also. Perhaps we should begin to rethink McCulloch as an artist who should be considered along with his Scottish contemporary William Dyce, who both influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and was in turn influenced by them. Dyce painted a number of notable Highland landscapes such as Christ as the Man of Sorrows from 1860.

[7] It is reproduced in photogravure (by Annan) not half-tone, and that further emphasises its role as a work of art.

[8] Glasgow Art Galleries and Museums. Painted in 1860.

[9] Scottish Reminiscences, 227.

[10] In collaboration with the Third Eye Centre, Glasgow.

[11] ‘Striking such a deathly pose’ The Herald, Friday 15 April, 2005, 21.

[12] Catriona Black, Sunday Herald, 17 April, 2005.

[13] Iain Gale, Scotland on Sunday, 17 April, 2005.

[14] Duncan Macmillan, The Scotsman, 19 April, 2005.

[15] My thanks to Lorna Waite for drawing my attention to this quotation.

[16] Alexander Carmichael (1905), Deirdire, Edinburgh: Norman Macleod, 139.

[17] James Storer and John Greig (1805): Views in North Britain Illustrative of the Works of Robert Burns, London: Vernor and Hood.

[18] See Murdo Macdonald, ‘Art and the Scottish Highlands: An Ossianic Perspective’. For Ossian Then and Now, a conference at Université Paris 7 and UNESCO, with the National Galleries of Scotland and Highland Council, Paris, 19 November 2005.

[19] The image may be the work of Robert Moyes Adam.

[20] Christopher Dingwall (1997) ‘Ossian and Dunkeld: A Hall of Mirrors’, Scotlands 4.1, 62-70.

[21] See F. R. Coles (1910), ‘Report on Stone Circles in Perthshire, Principally Strathearn: with Measured Plans and Drawings’ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Vol. IX, 4th Series, 1910-1911, pp. 46-116. The quotation from is from Thomas Newte (1791) building on the eyewitness account of Edward Burt, is taken from a note appearing on p. 97.

[22] Calanais catalogue, Stornoway: An Lantair, 68.

[23] My thanks to Finlay Macleod for drawing my attention to the work of Malcolm MacDonald.

[24] See, e.g. Richard Ingleby and Matthew Gale (1999) Two Painters: Works by Alfred Wallis and James Dixon, London: Merrell Holberton.

[25] See Dan Morrison (1997) Nis Aosmhor: The Photographs of Dan Morrison, Stornoway: Acair.

[26] Cover note, Poetry Scotland , No. 1, 1943.

[27] Ian Stephen’s Broad Bay is another of Finlay’s publications.

[28] Patrick Geddes (1920) The Life and Work of Sir Jagadis C. Bose, London: Longmans; chapter 8, ‘Holidays and Pilgrimages’.

2 thoughts on “Art, Maps and Books: Visualising and Re-visualising the Highlands [2006]”

Comments are closed.